Friday, July 31, 2009

sms pantun

kemana ajach lo ga’ pernah sms

anak tikus rindu ibunya

sombong nich ceritanya

ada kepompong ada kupu

bales donk sms dari aku

Mlam kian larut,wkt’y trik sLmUt,cCi kaki biar g da SmUt,jgn dngr lgu dangdut,tKUt nnti manggUt2,sLam dr Si iMUT,”Bismika allahumma ahya wabismika amuut”.

Pantun PERCAYA DIRI:

Buah SEMANGKA buah DUREN-

gak NYANGKA gue KEREN.

Buah MANGGA buah MANGGIS-

gak DISANGKA gue MANIS.

Ada GULA ada SEMUT-

ih GILA, gue IMUT2…

unknown

=====================================

abis dhuhur itu asar,

ucap janji itu nadhar

tetep menunggu itu sabar,

lagi usaha itu iktiar

yang bc sms ini apa kabar

Ke Ciamis Membawa Gitar,

Hai MAniez paKabar?

Pasar MInggu di Jakarta Selatan,

Ga ganggu kaN?

Ada Talas dan Kedondong,

Bales dong?…………

ada pacar…

tp tercampakan…

ada cinta…

tapi TerNodai…

ada Sayang…

tapi terSisih…

Tapi kalo ada Daki..

Buruan Mandi…!!!

Monday, July 27, 2009

Sexual health and HIV.

Maintaining and promoting good sexual health is not only important for preventing sexually acquired infections and unintended pregnancies, but also for the prevention of transmission and acquisition of resistant strains of HIV, hepatitis C, preventable infertility and anogenital cancers [1]. Sexual health, although having been in the spotlight for a long time [2], has primarily focused on sexual infection and disease prevention [3]; however, this focus is now shifting to become more inclusive of other aspects of human sexuality. It now encompasses the broad spectrum from sex education in schools [4] to sexual function, in part because of the HIV epidemic and its associated research. Poor sexual health disproportionately affects men who have sex with men (MSM) and women [1], and in the UK the focus is now on developing a sexually healthy society, with a large number of government initiatives and standards set by health organisations [5-8].

Sexual health is not a timeless concept [9] and the definition is broad; however, there are a number of definitions and three overarching themes [10]:

* The capacity to enjoy and control sexual and reproductive behaviour in accordance with a social and personal ethic;

* Freedom from fear, shame, guilt, false beliefs and other psychological factors inhibiting sexual response and impairing sexual relationship;

* Freedom from organic disorders, disease and deficiencies that interfere with sexual and reproductive functions.

Assessing sexual health

A sexual history should be taken on a 6-monthly basis and patients should be offered annual sexual health screens [11]. Patients engaging in high-risk behaviours and those with symptoms should be offered a check-up more regularly. Risk-taking behaviours and barebacking are common: one in three MSM engage in unprotected anal sex [12]. While being essential to identify and discuss, it is important to approach sexual risk-taking and drug use with sensitivity, as a judgemental approach will alienate and become a barrier for people attending services for diagnosis and treatment [9,12,13]. Routine sexually histories should identify potential sites of infection and include questions about sexual practices that may increase the likelihood of transmission of infections: multiple sexual partners, drug use for sex, unprotected intercourse, the use of sex toys that are shared and shared lubricant when sex involves multiple partners. A travel history is also useful.

Screening

Asymptomatic patients should have routine checks for gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C. Always ensure that patients are up to date with their hepatitis A and B vaccinations and, if vaccinated, annual checks of their anti-HBs to ensure adequate protection. Routine examination should include the skin, oral cavity, anus, vagina or penis and testicles. Patients with symptoms should be screened dependent on symptoms as per national guidelines [14]. However, in routine presentations a high index of suspicion for the unusual should always be exercised in patients engaging in high-risk behaviours given the increases in previously uncommon conditions such as LGV and irregular presentations of conditions such as syphilis. Atypical anogenital lesions should be referred for assessment to exclude pre-cancerous changes (intraepithelial neoplasia) or other chronic dermatological complaints.

Women and HIV

It is recommended that women with HIV should have an initial colposcopy at diagnosis followed up with annual cervical cytology [11]. Contraception is as important as it is for negative women; however, consideration is required for interactions with antiretroviral therapy. For example, as liver enzyme-inducing medication such as atazanavir increases the metabolism of progesterone-only emergency contraception, a woman would require double the dose of the contraception [15]. Pre-conceptual care and pregnancy services are also necessary as specialist advice or support may be required for interventions such as sperm washing, changes in treatment and support post delivery.

Sexual function

Sexual function issues are common in patients with HIV [16]. This is hardly surprising given the psychological and physical impact that HIV can have--the diagnosis itself, the fear of transmission, altered body image, stigma, fear of rejection, discordant relationships, loss of a partner, the impact of the disease on the body, the various medications and co-infections, to name but a few. Untreated sexual dysfunction may cause other issues, including unprotected anal sex because of erectile dysfunction as it is difficult to use condoms, or complete avoidance of sex and forming attachments, so impacting on quality of life. Assessments of patients should include questions about sexual function, with referral to specialist services as appropriate. Do make sure, however, you understand what is available before assessing sexual function as it is a little unfair to raise a patient's expectations and not be able to follow through with appropriate interventions.

Raising status issues

Discussing HIV status with prospective partners is fraught with potential problems and issues of rejection, stigma and potentially violence [9]. As well as 'killing the mood', stigma may lead to low self-esteem, which in itself can lead to increased sexual risk-taking [9]. However, talking about HIV status in a discordant relationship can lead to both partners working hard to maintain the negative partner's negativity [17]. Where both partners are HIV-positive, it is also important for sexual partners to broach status issues of resistant HIV and hepatitis C, especially if they are planning to engage in unprotected sex.

Legal issues

Since the successful prosecution of a man in Scotland in 2001 [18], there have been relatively few prosecutions for reckless transmission of HIV. However, it is important to discuss with patients the potential legal issues if they are engaging in risky sexual behaviours. There is a wide assumption of safety from prosecution if you inform your negative or untested partner of your HIV status prior to unprotected sex [19]. The law can also apply to other infections [20], although there have been no successful prosecutions as yet [19]. This has potential implications for HIV-positive patients who are co-infected with hepatitis C or infections like herpes, or have resistant strains of HIV.

Health promotion and protection

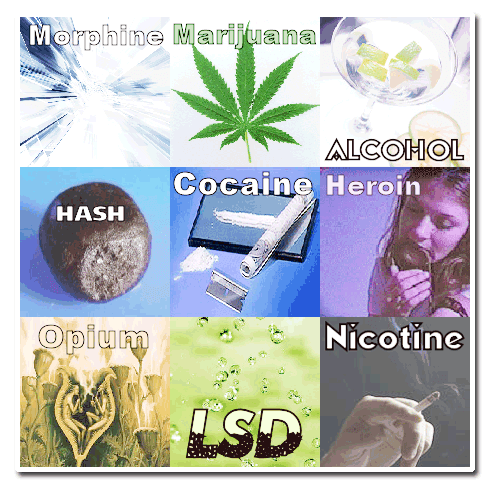

When working with patients it is important to discuss post-exposure prophylaxis for sexual exposure (PEPSE), ensuring that they are aware of when it should be used and how it can be accessed especially out of hours. Also (where indicated) discussions should occur relating to risk-taking behaviours, drug use (including alcohol and smoking), resistant HIV and hepatitis C.

Implementing sexual health initiatives

When implementing initiatives it is important to make them as seamless as possible for the patient and, where possible, involve patients in the planning stages. It is also best to avoid, where possible, extra clinic visits, referrals to various other professionals/services and multiple long waits. It may be easier and more convenient for the patient to have any further tests incorporated into their routine blood screens/appointments. Using proformas can standardise care and make auditing easier for clinicians. The use of questionnaires that patients fill in can also speed up the process (especially for asymptomatic patients). This can be supported with prompts on computer systems or in the patients' notes. If local sexual health contraceptive services are not co-located/ integrated, developing links is very helpful.

Further reading

Sexual function

Bancroft J. Human Sexuality and its Problems. 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 1989.

Barebacking

Halkitis P, Wilton L, Drescher J. Barebacking: Psychosocial and Public Health Approaches. Haworth Medical Press, New York, 2005.

Sexually transmitted infections

Pattman R, Snow M, Handy P, Sankar K, Elawad B. Oxford Handbook of Genitourinary Medicine, HIV and AIDS. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005.

Clinical skills

Grundy-Bowers M snd Davies J. Advanced Clinical Skills for GU Nurses. Wiley, London, 2007.

Contraception

Guillebaud J. Contraception: Your Questions Answered. Churchill Livingstone, London, 2008

References

[1] Kinghorn G. A sexual health and HIV strategy for England. BMJ, 2001, 323, 243-245.

[2] Grundy-Bowers M. Defining advanced practice. In Advanced Clinical Skills for GU Nursing (Grundy-Bowers M and Davies J, eds), Wiley, London, 2007.

[3] Rosenthal D and Dowsett G. The changing perceptions of sex and sexuality. Lancet, 2000, 356, 58.

[4] Coyle K, Baen-Engquist K, Kirby D et al. Short-term impact of safer choices: a multicomponent, school-based HIV, other STD, and pregnancy prevention program. J Sch Health, 1999, 69, 181-189.

[5] Department of Health. The National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV. Department of Health, London, 2001.

[6] Department of Health, Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. Department of Health, London, 2004.

[7] Medical Foundation for and Sexual Health. Recommended Standards for NHS HIV Services. MedFASH, London, 2003.

[8.] Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health. Recommended Standards for Sexual Health Services. MedFASH, London, 2005.

[9.] Vanable P, Carey M, Blair D, Littlewood R. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviours and psychology adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav, 2006, 10, 473-482.

[10.] Mace D, Bannerman R, Burton J. The teaching of human sexuality in schools for health professionals. WHO Public Health Papers, No 57, 1974. WHO, Geneva. Cited in Edwards W, Coleman J. Defining sexual health: a descriptive overview. Arch Sex Behav, 2004, 33, 189-196.

[11.] British HIV Association. Standards for HIV Clinical Care. BHIVA, London, 2007.

[12.] Richard M. Sexual health: one in three HIV-positive gay men have unprotected sex. Practitioner, 2007, May 28, 33.

[13.] Valdiserri R. HIV/AIDS stigma: an impediment to public health. Am J Public Health, 2002, 92, 341-343.

[13.] BASHH National Guidelines. www.bashh.org/guidelines (last accessed 25/09/2008).

[15.] Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Faculty statement from the CEU on Levonelle 1500 and the use of liver enzyme inducing drugs. 2006. www.ffprhc.org.uk/admin/uploads/563_Levonelle1500KeyStatement.pdf (last accessed 25/09/2008).

[16.] Lamba H, Goldmeier D, Mackie N, Scullard G. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with sexual dysfunction and increase serum oestradiol in men. Int J STD AIDS, 2004, 15, 234-237.

[17.] Hong D, Goldstein R, Rotheram-Borus R et al. Perceived partner serostatus, attribution of responsibility for prevention of HIV transmission, and sexual risk behaviour with 'main' partner among adults living with HIV. AIDS Educ Prev, 2006, 18, 150-162.

[17.] AIDSmap website. www.aidsmap.com/en/news/D5C5C7B8-0D45-44BA-9284-BAD743EFE3D0.asp (last accessed 25/09/2008).

[19.] The Eddystone Trust website. www.eddystone.org.uk/hiv07/hiv_pages/prosecutions.php (last accessed 25/09/2008).

[20.] Crown Proscution Service website. www.cps.gov.uk/legal/section5/chapter_g.html (last accessed 25/09/2008).

Single Sex Education

BENEFITS

In 1992, a report issued by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) stated that girls faced widespread bias in classrooms across the United States. In the report, "How Schools Shortchange Women," researchers surveyed more than one thousand previous studies and articles on girls and education. Among the key findings cited in the report were the following:

- Girls continued to score lower than boys on standardized tests in mathematics and science, even though their grades in the classroom tended to be higher.

- Teachers called on boys more often, gave them more detailed criticism and allowed them to shout out answers while reprimanding girls for doing the same.

- Few girls chose to pursue careers in math or science, and few teachers encouraged them to do so.

- Many textbooks continued to stereotype women and failed to address issues of concern to women, such as discrimination and sexual abuse.

Although the report was designed to encourage a change in behavior in the co-ed classroom, the report was read by many as a mandate to pursue single-sex education.

Court Battles

In the following years, the media focused on how several states, specifically New York and California, experimented with gender-segregated public schools. Both the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Organization for Women (NOW) bitterly opposed the concept and began fighting the battle in the courts. Many educators who work in all-girls' schools say that they make a positive difference in the social, intellectual, and academic development of the girls. Studies highlighting the benefits were questioned as to whether the improvement is a result of smaller classes and academic rigor or if the absence of boys truly made a difference.

A New Study

In 1998, the AAUW released another study, "Separated by Sex: A Critical Look at Single-Sex Education for Girls." The report noted that since 1991, the student population of all-girls' schools grew from 29,000 to 38,000. Without conducting new research, but merely reviewing the existing literature, the report essentially concluded that if public schools could become more like private schools, girls would receive a better education without having to be separated from boys.

VMI

Despite the encouraging results, proponents of single sex education found themselves embattled when it came to schools that used public funds. Cries of violations of civil rights in terms of equal protection guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment led many arguments to the courts. The issue extended to the level of higher education. In 1996 the Supreme Court ruled that the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) must begin admitting women after 157 years of a male-only student body. The academy was one of the last remaining single-sex colleges in the country that accepted state funds. Private schools, however, continued to find a market for parents who believed that separating the genders allowed students to focus on their academic needs without the constant distractions of their social desires.

PIKR

Informasi tentang kesehatan reproduksi remaja (KRR) bagi remaja maupun keluarga yang mempunyai anak remaja dirasakan kurang, hal ini dikarenakan oleh beberapa factor antara lain kurangnya materi KIE KRR, frekwensi KIE masih kurang, belum adanya tempat konsultasi yang dapat dijadikan sebagai pusat rujukan konsultasi kesehatan reproduksi remaja (KRR).

Salah satu upaya untuk menyebar luaskan dan mengembangkan isi pesan kesehatan reproduksi remaja (KRR) di Kabupaten Bandung dibentuk dan dikembangkan Pusat Informasi dan Konsultasi Remaja (PIKR).

1.2 TUJUAN

1.2.1 Tujuan Umum

Meningkatkan pelayanan program kesehatan reproduksi remaja melalui pembinaan dan pengembangan pusat informasi dan konsultasi remaja.

1.2.2 Tujuan Khusus

1. Meningkatkan pengetahuan para pengelola program dalam membina dan mengembangkan PIKR.

2. Meningkatkan jaringan informasi KRR.Tersedianya wadah bagi para remaja maupun kelearga yang memiliki anak remaja untuk mendapat pelayanan informasi dan konsultasi KRR.

1.3 PENGERTIAN

Pusat Informasi dan Konsultasi Remaja (PIKR) adalah wadah bagi para remaja maupun keluarga yang mempunyai anak remaja untuk mendapatkan informasi atau berkonsultasi tentang masalah kesehatan reproduksi remaja (KRR).

Kesehatan Reproduksi Remaja (KRR) adalah suatu kondisi sehat yang menyangkut system, fungsi dan proses reproduksi yang di miliki oleh remaja. Pengertian sehat tidak semata-mata bebas dari penyakit atau bebas dari kecacatan, namun juga sehat secara mental, serta social budaya.

Remaja adalah individu baik perempuan maupun laki-laki yang bereda pada masa/usia antara anak-anak dan dewasa. Adapun batasan remaja berdasarkan :

BKKBN (Badan Koordinasi Keluarga Berencana Nasional) adalah penduduk laki-laki atau perempuan yang berusia 10 – 19 tahun dan belum menikah.

WHO (World Health Organization ) adalah penduduk laki-laki atau perempuan yang berusia 10 – 19 tahun.

UN (United Nation) menyebutnya sebagai anak muda (youth) untuk usia 15 – 24 tahun. Ini kemudian disatukan dalam batasan kaum muda (young people) yang mencakup usia 10 – 24 tahun.

1.4 SASARAN

1. Remaja

2. Keluarga

3. Tokoh masyarakat, tokoh agama, tenaga professional (Bidan, Dokter, Psikolog, dsb)